How to stop engineering prompts and start delegating

TL;DR: The best “prompt engineering” technique isn’t engineering at all—it’s delegation. Transfer intent, not instructions. For quick tasks, tell the AI what success looks like and why (the Intent Prompt). For complex work, equip it with context, deliverables, and decision principles so it can navigate on its own (the Delegation Brief). You already have these skills. This post helps you apply them to AI.

Here’s something that recently “clicked” for me:

Generals briefing troops before a mission. Ad agencies briefing creatives on a campaign. Amazon teams writing tenets to align on strategy. Simon Sinek on a TED stage asking “Why?”

They all work in wildly different domains. They never compared notes. And yet every single one of them arrived at the same structure for getting what’s in one person’s head into another person’s actions.

It’s a simple idea: transfer intent, not instructions. Tell the agent, human or AI, what success looks like and why it matters. Give them enough context to navigate on their own. Then get out of the way.

This turns out to be the most effective way to work with AI as well: Not because someone engineered it for prompting, but because it solves a universal delegation problem that’s centuries old.

If you want the short, 8 minute video version, here it is:

On the the part about more background and details:

I stumbled into this connection while reading Ethan Mollick’s article Management as AI Superpower. In it, he describes how his MBA students—doctors, managers, company leaders—built working startup prototypes in four days using AI tools. They weren’t AI experts, but they’d spent years learning how to scope problems, define deliverables, and recognize when output was off. Their management skills became their prompting skills.

Mollick also mentioned an interesting reference: the military’s Five Paragraph Order, a structured briefing format, works remarkably well as an AI prompt template. Now, I’m a pacifist, but I have to admit that they must know what they’re doing, given the high-pressure, high-stakes environment the military operates in. That got me thinking. If the military solved delegation under pressure, who else did? And do they have something in common?

They do.

You already know how to do this

Here’s the thing most “prompt engineering” advice gets wrong: it treats prompting as a technical skill—a set of tricks, magic words, and secret formulas. “Use these 7 words to unlock hidden power.” “Add ‘think step by step’ to every prompt.” The framing makes it sound like you need a PhD in AI to get good results.

You don’t. What you need is something you already practice every day.

Every time you’ve briefed a colleague on a project, scoped work for a contractor, or explained what “done” looks like to a new hire—you were doing exactly what effective AI prompting requires. The skill isn’t technical. It’s managerial. And the shift we need isn’t from bad prompts to good prompts. It’s from instructions to intent.

“I want you to write a professional email” is an instruction. “I need a reply that signals support but flags the timeline risk, because I want to stay aligned without silently agreeing to an unrealistic deadline”—that’s intent. The first tells the AI what to do. The second tells it what success looks like and why. And that makes all the difference.

This is Commander’s Intent. This is Start with Why. This is Working Backwards. And it works for the same reason across all of them: intelligent agents, whether human or AI, perform better when they understand the purpose behind the task.

The landscape: why context matters

Let’s imagine the AI’s knowledge as a vast dark landscape. Everything it absorbed during training, from programming to poetry to business strategy. Then, your prompt is like a light source, illuminating the possible paths your AI can take as it processes your request.

A vague prompt is a dim floodlight: everything is faintly visible, nothing is in focus, so the AI picks the most “average” path through the possibilities. A specific prompt is a focused beam that illuminates the terrain between where you are and where you need to arrive.

I think about this every time I craft a prompt. It’s like finding a route in a mapping app: the AI will happily suggest multiple paths, but the more I tell it about the terrain, like “my audience is tech professionals,” “feel free to push back if you disagree,” “use a casual tone”, the more it narrows down to the route I actually want. I’m not giving step-by-step directions. I’m lighting up the landscape so it can find the right path on its own. Even my favourite trick, inviting people I admire virtually into the AI chat, is about highlighting their thinking patterns so I can get results that leverage their mental models.

Two things sharpen the beam. First, activating knowledge the AI already has. “My audience is skeptical CTOs at mid-sized companies” doesn’t teach the AI anything new—it points the beam at expertise the model already has. Second, providing knowledge the AI can’t have. Your specific data, your previous work, your constraints—these place new landmarks on the map that weren’t there before.

This is why the same AI produces brilliant work for one user and generic mush for another. It’s not inconsistency. It’s illumination. Prompt quality isn’t about tricks or magic words. It’s about how well you light up the territory between where the AI starts and where you need it to arrive.

The Intent Prompt: for quick tasks and tight feedback loops

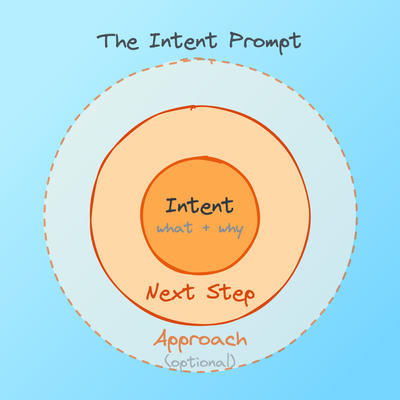

For most everyday interactions, you just need two things.

Intent: What does success look like, and why does it matter? Be concrete enough that both you and the AI could verify whether the output hits the mark.

Next Step: What should the AI do right now? This keeps things iterative. You’re not asking for the whole journey, just the first move.

Optionally, hint at an Approach: “I’m thinking a direct but warm tone” or “maybe start with the data and work toward conclusions.” A suggestion, not an order.

That’s it. One to three sentences. Notice how the intent statement naturally embeds context—the audience, the constraints, the tone—without needing separate sections. When your intent statement gets overloaded with context, that’s a signal to graduate to a more complete “Delegation Brief”, which we’ll talk about in a minute.

Here’s what good Intent Prompts look like in practice:

Before: “Write me a LinkedIn post about AI.”

After: “I want a LinkedIn post that challenges the ‘prompt engineering’ hype and positions delegation skills as the real AI superpower. My audience is mid-career tech professionals who are skeptical of AI buzzwords. Conversational authority, not guru vibes. Draft it.”

Before: “Summarize this article.”

After: “I’m deciding whether to reference this article in a blog post about AI delegation. I need to know: what’s the core claim, what evidence supports it, and is there anything I should fact-check? Give me a quick assessment.”

Before: “Help me reply to this email.”

After: “My colleague proposed an aggressive Q3 timeline I think is unrealistic. I need a reply that acknowledges the ambition, supports the direction, but creates space to revisit the dates, without sounding like I’m blocking progress. Draft it.”

It’s not about longer prompts (although giving more information certainly helps). The core idea is intent. Each “after” version tells the AI what the finish line looks like and why it matters. The AI can now make good micro-decisions along the way—tone, structure, emphasis, what to include and what to leave out, because it understands the purpose.

When should you use a full Intent Prompt vs. just typing a quick question? Think about it this way: if the task would take you significant time to do yourself, spending thirty seconds to articulate clear intent pays for itself many times over. If it’s a quick question you’ll evaluate instantly—just ask.

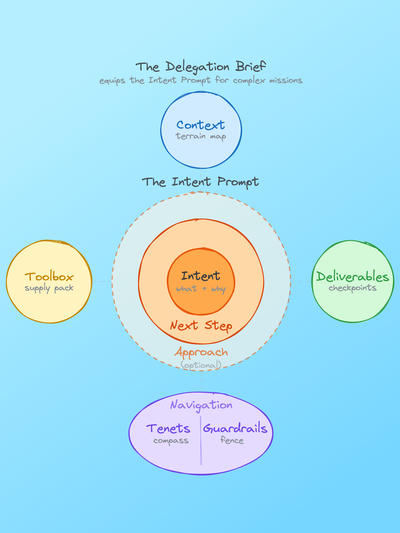

The Delegation Brief: for when AI needs to navigate on its own

The Intent Prompt works great when the feedback loop is tight: you ask, you review, you iterate. But what happens when you expect the AI to make multiple decisions on its own? When it needs to navigate a larger territory, like writing code for a new feature, performing a comprehensive analysis, producing a full document with many moving parts?

Some tasks are too big for a single sentence of intent. When the AI needs to make dozens of autonomous decisions across multiple steps and you can’t review every micro-output, then you need to equip it properly.

It’s like sending your AI on an expedition: larger scope requires more autonomy, and more autonomy requires better equipment.

This is especially true for agentic AI tools like Claude Code, Claude Cowork, Cursor, and similar coding or knowledge-work agents that run for minutes or hours without checking in. Nobody would send an employee on a month-long project with a single sentence of instruction. The same applies here. The Delegation Brief provides five building blocks, each one serving a specific need:

Intent — the destination beacon

This is the same as the Intent Prompt, possibly more detailed. The concrete end state and why it matters.

Ask yourself: “If I could only tell the AI one sentence about what I need, what would it be? Can I describe what ‘done’ looks like in a way we could both verify?”

Context — the terrain map

Everything the AI needs to avoid making wrong decisions. This is separated out because it’s too rich to embed in the intent statement.

Ask yourself: “What would a smart new colleague need to know on their first day to not embarrass themselves on this project?”

This may include audience and stakeholders, existing work, prior decisions, constraints, what’s been tried before, and anything about the landscape—political, technical, social—that shapes what “good” looks like.

Deliverables — the checkpoints

What specific outputs, in what format, at what intermediate review points. This turns a vague mission into something verifiable.

Ask yourself: “What do I want to receive, and when do I want to check in before the final result?”

For longer missions, include waypoints: “Give me the outline first, then we’ll proceed to the full draft.” This is your steering mechanism.

Navigation — the compass and the fence

Here are two instruments that serve the same purpose in complementary ways: enabling autonomous movement through unfamiliar territory.

Tenets: these are decision principles. They tell the AI which way to go when it faces a trade-off. “Concise over comprehensive.” “My voice, not AI-generic.” We’ll discuss them in more detail below, because they’re the most powerful part of the framework.

Guardrails: hard boundaries and escalation triggers. “Stop after the outline for my review.” “Don’t exceed 12 minutes of script.” “If you’re uncertain about a factual claim, flag it rather than guessing.”

The difference is like two sides of the same medal: tenets help the AI gravitate towards good decisions. Guardrails prevent catastrophic ones.

Ask yourself: “What trade-offs will the AI face repeatedly?” (tenets) and “What would make me say ‘you should have checked with me before doing that’?” (guardrails)

Toolbox — the supply pack

Examples of what good and bad output looks like. Reference materials, links, data. Approach suggestions. Random ideas or inspiration. Attach whatever helps—this enhances any building block without being a building block itself. I often end up braindumping random thoughts that Claude then helps me clear up here.

A full example

Say you’re kicking off a Claude Code session to build a personal finance dashboard. Here’s what the Delegation Brief might look like:

Intent: “Build a personal finance dashboard that pulls transactions from a CSV export, categorizes spending automatically, and shows me month-over-month trends. I want to finally understand where my money goes without wrestling with spreadsheets every month. It should feel snappy and look clean enough that I’m not embarrassed to show it to my partner.”

Context: “I’m a competent developer but not a frontend specialist—React is fine, anything fancier will slow me down. The CSV comes from my German bank, so expect Euro amounts, German date formats (DD.MM.YYYY), and semicolon delimiters. My wife will use this too, so it needs to be intuitive without a manual. We’ve tried the bank’s own web interface and popular tools before but they felt like too much overhead for what we actually need.”

Deliverables: “A working local app I can run with a single command. Start with the data import and categorization logic—show me that working first before building the UI. Include a README that my wife could follow to get it running.”

Navigation:

- Tenets: “Simple over feature-rich—I’d rather have three things that work than ten that almost work.” “Readable code over clever code—I’ll be maintaining this myself.” “Useful defaults over configurability.”

- Guardrails: “No external APIs or paid services—this runs entirely local. Stop after the data pipeline works for my review before building the frontend. If a categorization rule seems too fragile, flag it.”

Toolbox: “Here’s a sample CSV export from my bank. For the UI, think nice and clean category breakdown like if Apple designed it—just the spending pie chart and the trend lines.”

Notice how each building block answers a distinct question the AI would otherwise have to guess at. That’s fewer wrong turns, fewer revisions, and a dramatically better first output.

Now, I know what you might be thinking: that’s a lot of writing just to start a task. Fair point. But consider two things. First, this upfront investment saves you hours of back-and-forth later: the more autonomous the AI needs to be, the more the brief pays for itself. And second, here’s the good news, you don’t actually have to write this all by yourself. More on that in a moment.

Tenets: the secret sauce

Of all the building blocks, tenets deserve a deeper look—they’re the least obvious and the most powerful.

I borrowed this concept from Amazon, where I spent 12 years. At Amazon, teams define 5–7 prioritized principles that act as tie-breakers in daily decisions. In a talk on Amazon’s decision-making culture, Llew Mason, VP at Amazon, explains their purpose: tenets help teams “avoid having to have management overhead of asking permission to do things.” The team charter explains what they do. The tenets explain how they decide.

Sound familiar? That’s exactly the problem with AI agents that keep pausing to ask, “Should I do X or Y?” Every time the AI interrupts you with a clarification, it’s hitting a decision point where it lacks a tenet to guide it.

What makes a good tenet

Amazon has a quality test that maps well to AI interaction: a good tenet has a meaningful opposite. If nobody would argue the other side, it’s not a tenet—it’s a truism.

“Produce high-quality output.” Who would argue against that? Everybody wants high-quality. Where’s the tradeoff? It doesn’t help the AI decide anything.

“Concise over comprehensive” Now that’s a real choice. Someone could legitimately prefer “comprehensive over concise.” This tenet tells the AI exactly how to resolve the tension it faces every time it considers adding another paragraph.

Good tenets come in recognizable forms, like “X over Y.” “A, not B.” Counter-intuitive beliefs that signal what you value.

Here are some tenets I’ve found useful, organized by the trade-offs they resolve:

Communication: “My voice, not AI-generic.” “Concise over comprehensive.” “Show, don’t tell—use examples over abstract explanation.” “Plain language over jargon, even for technical topics.”

Decision-making: “If it can be tested without harm, test it.” “When in doubt, ask—don’t guess.” “Progress over perfection.” “Solve the problem in front of us, not the general case.”

Truth and quality: “Truth-seeking over user-pleasing. Push back when something seems wrong.” “Surface problems eagerly.” “Admit uncertainty explicitly rather than hedging with vague language.”

Each one has a meaningful opposite that someone could legitimately prefer. That’s what makes them useful: they resolve real trade-offs that the AI faces dozens of times per response.

There’s likely a good place for tenets already in your AI tool—you don’t have to put them inside every prompt. Most AI tools give you a place to store them persistently. If you use Claude Code or Cursor, that’s your CLAUDE.md or project-level instructions file. If you use Claude.ai, it’s your Projects instructions or the “preferences” section in settings. ChatGPT has Custom Instructions. Most chat-based AI tools have some version of “about me” or “how should Claude respond” where your tenets naturally belong. Set them once, so they can shape every interaction without repeating yourself.

It’s worth noting that Anthropic’s own guidelines for Claude (system prompts, and the recently revealed soul document) are essentially a massive set of tenets with priority ordering—principles that tell the model how to resolve conflicts between competing goals. Users can create their own version at a personal level.

Too much work? Let AI build the brief for you!

The Delegation Brief is powerful, but assembling one from scratch for every complex task would get old fast. Here’s where this framework becomes practical: you don’t have to build the brief alone. Let the AI do it for you.

You can approach this way of prompting in three stages. First, try out writing Intent Prompts for simple tasks. It’s easier and more intuitive than you might think—just focus on the end result you want to achieve and why. That alone will change your AI productivity forever. Second, try adding more and more Delegation Brief building blocks so you can see how they improve your results for more complex tasks. Third, and this is the real kicker: give the AI your rough intent and let it interview you to build the full Delegation Brief.

Try something like: “I want to create a comprehensive onboarding guide for our new engineering hires. Before we begin, interview me to build a complete brief—ask about context, deliverables, tenets, and guardrails.”

The AI will ask smart questions about your audience, constraints, format preferences, and decision principles. Within a few minutes, you’ll have a complete brief—one that took a fraction of the effort but captures far more than you’d have thought to include on your own.

This is actually the strongest validation of the framework: even when the AI helps create the brief, it needs to know what to ask for. The building blocks work as both a template for humans to fill in and a checklist for AI to use when clarifying requirements.

To make this even easier, I’ve created a ready-to-use Delegation Brief Builder prompt as a GitHub Gist, so you can install in your favorite AI tool. Grab it here. And if you use Claude Code or the Claude.ai app, here’s a full Delegation Brief Builder skill you can install, complete with decision tree (Intent Prompt or Delegation Brief), building blocks and guidance on formulating tenets.

Note: as of today (2026-02-17), there’s a bug with how the Claude Desktop app is handling skills, so, while I have carefully reviewed all of the skill’s files and they should work, I didn’t have the opportunity yet to test it, since I seem to be affected by this bug. I’ll update my post once this is resolved. Meanwhile, use the prompt in the gist mentioned above, which does work well. If you get it to work and can provide me feedback on how well it works, please let me know!

You already have the skills

Mollick’s MBA students succeeded not because they were AI experts. They succeeded because they knew how to scope problems, define what “done” looks like, and recognize when a financial model or medical report was off. Their years of management training, it turned out, was accidentally preparing them for exactly this moment.

The framework in this post isn’t new knowledge. It’s an explicit way of doing what effective delegators have always done, whether they were briefing troops, creatives, product teams, or algorithms. The military calls it SMEAC. Ad agencies call it the Creative Brief. Amazon calls it Working Backwards. Every field that depends on delegation under pressure arrived at the same essential structure, because it addresses a fundamental truth about how intelligent agents do their best work, whether they’re human or AI.

The shift from “prompt engineering” to “delegation” isn’t just a reframe. It’s a recognition that the skills that matter most for working with AI are the ones humans have been developing for centuries: knowing what good looks like, communicating it clearly, and trusting your agent to find the path.

Here’s what I’d suggest: try the Intent Prompt on your next simple AI task. Just add the “why” and a concrete description of what success looks like. Then try the full Delegation Brief on your next complex one. Start building your personal tenets. Begin with three that reflect how you want AI to work for you.

You don’t need to learn prompt engineering. You already know how to delegate. Now you have the words for it. 🎯

This post was inspired by Ethan Mollick’s “Management as AI Superpower.” The convergent frameworks referenced include the military’s Five Paragraph Order and Commander’s Intent, the advertising industry’s Creative Brief, Amazon’s Working Backwards process and Tenets, and Simon Sinek’s Start with Why.

Edit: (2026-02-21) Adding YouTube video version at the top.